: For this final interview of the first year in the VR is Alive Series, we are fortunate to join Dr. Ruth Diaz (she/they) earlier this year to chat about her vast experience as a social scientist inside and outside of multiple social virtual reality platforms, visiting virtual worlds she designed or recognized along the way...

ArmaniXR: Please introduce yourself with your pronouns and what you want the audience to know about you first.

Ruth: Oh, okay, so Ruth Diaz, pronouns are she/they. What I want people to know about me is...first of all, I am a human being. Human on purpose. I am a human on a quest to support the world and all the worlds, both in physical and virtual reality, to understand and practice conflict resiliency.

Can you tell me about your introduction and your earliest memory of social VR?

Yeah, I mean, I think the first understanding that we could be surrounded in a digital immersion experience was probably with the Mario Tennis experience on the Virtual Boy. It was like a virtual reality (VR) headset on the table back in 1996 or something. You would put your head in it, and you could play this very pixelated version of Super Mario playing tennis. That was fascinating to me—to feel my sense of self land on Super Mario. I wasn’t me anymore. I was this little, very pixelated being running around, trying to keep up with the AI that was playing.

It was a small experience, but I think it influenced me because I realized you could be dreaming while you were awake, forgetting that you had a body, a name, or any identity at all. I wasn’t particularly excited about that, but it felt like a note to self: This is possible. This is different.

My brother, who owned that Mario Tennis setup, later got the first Oculus Rift when it came out. When I visited him, it felt like we traded experiences. I went to see him at his home before we went on a road trip to visit our father, who he and the rest of the family had been estranged from for over 20 years. I needed someone else in my family to witness what I had seen—that this villain of our childhood, who used to be this giant, violent man, very mystical but also harmful at times, had become a fragile, old man. I needed someone else to see that and understand how important it was to see the humanity in the villains of our lives, and not be bound by the image of a giant monster. When you're four feet tall and there's a six-foot person who's violent and abusive, they seem like a giant monster.

But when we met up with him on that journey, we both realized we were almost taller than him at that point. My brother and I, standing at about five-eight or five-ten, saw how much he had shrunk. He was fragile and his memory was fading. It was my gift to my brother because I think he had the worst version of our dad projected onto him. I also shared with him this conflict resiliency model I had developed. I said, "Hey, I’ve developed this model that explains conflict in a way that has unlocked so much about my life, and it seems to have a powerful impact on everyone I show it to."

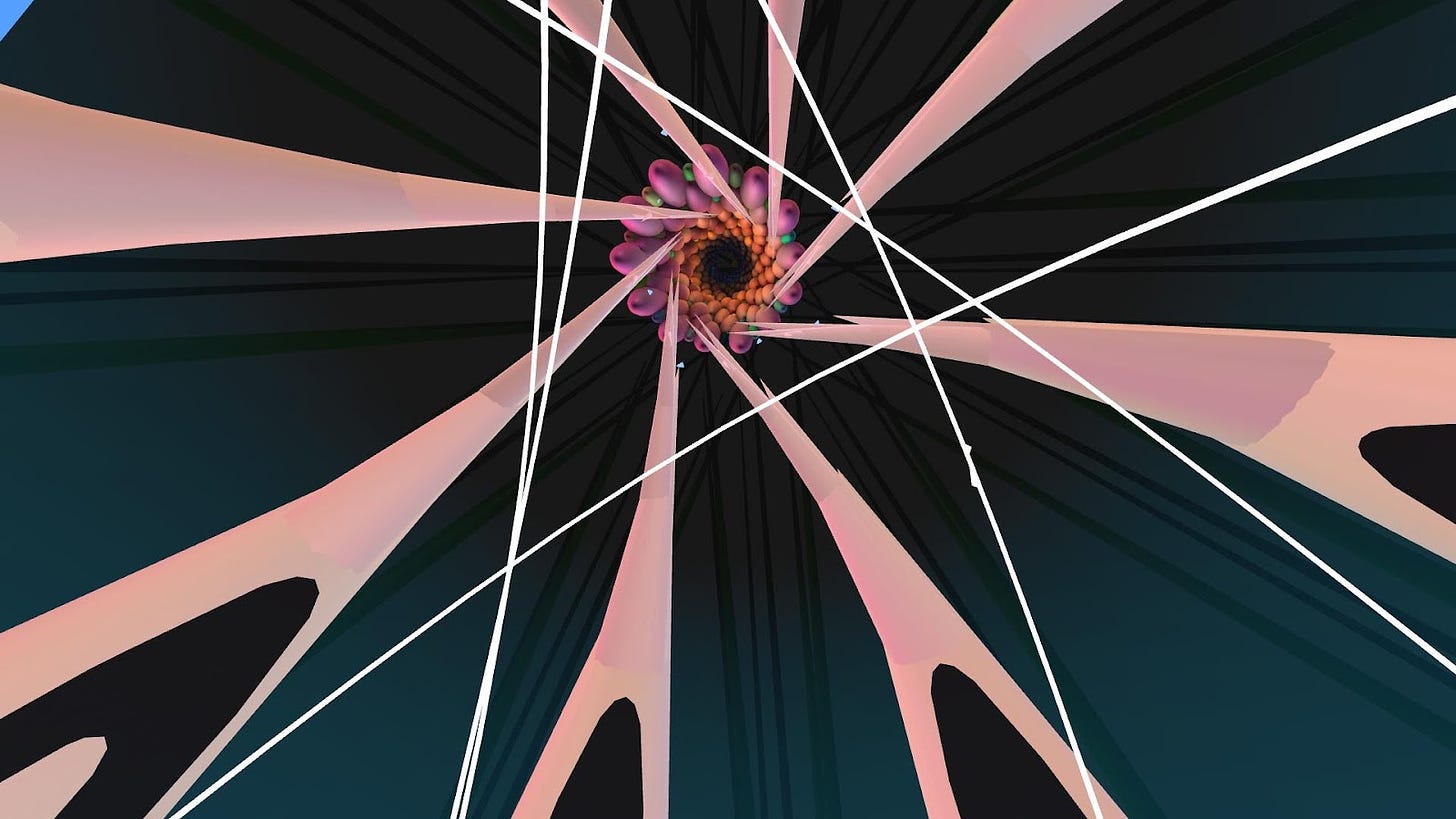

In return, my brother showed me the latest version of VR. At that time, my pain point was thinking that my model was a three-dimensional concept, but I was having to draw it on whiteboards and create PowerPoints. I wanted to stand around it, look at it from different angles, and play with it. He said, "I bought this Rift, it’s my new gaming toy," but he had other goals in life and had been sucked into VR. A few weeks after my visit, he sent me his whole system. It was like a sacrifice, as he knew I had discovered something important and wanted to empower me.

In a way, I felt like I had traded this fragile, non-villainous, broken human version of my father for this unexpected journey down the VR rabbit hole. I didn’t go there wanting or wishing for it, but it was probably the one gift my brother gave me that led to a profound new path. I wouldn’t have initiated this journey on my own, but since it was offered to me, I moved with it, exploring what I could figure out.

For the first year, it was a very isolated journey—learning the technology, trying different art apps, and understanding how to use them. Eventually, I got really lonely. I had built my model in different apps, but I didn’t have anyone to share it with, to test if it would have the same effect on them, hopefully even more powerful and intuitive than on a 2D screen. That’s when I started falling into social VR, searching for people who wanted to enter that space—not just to distract and entertain themselves, avoiding their physical lives—but maybe to change a little and learn something new.

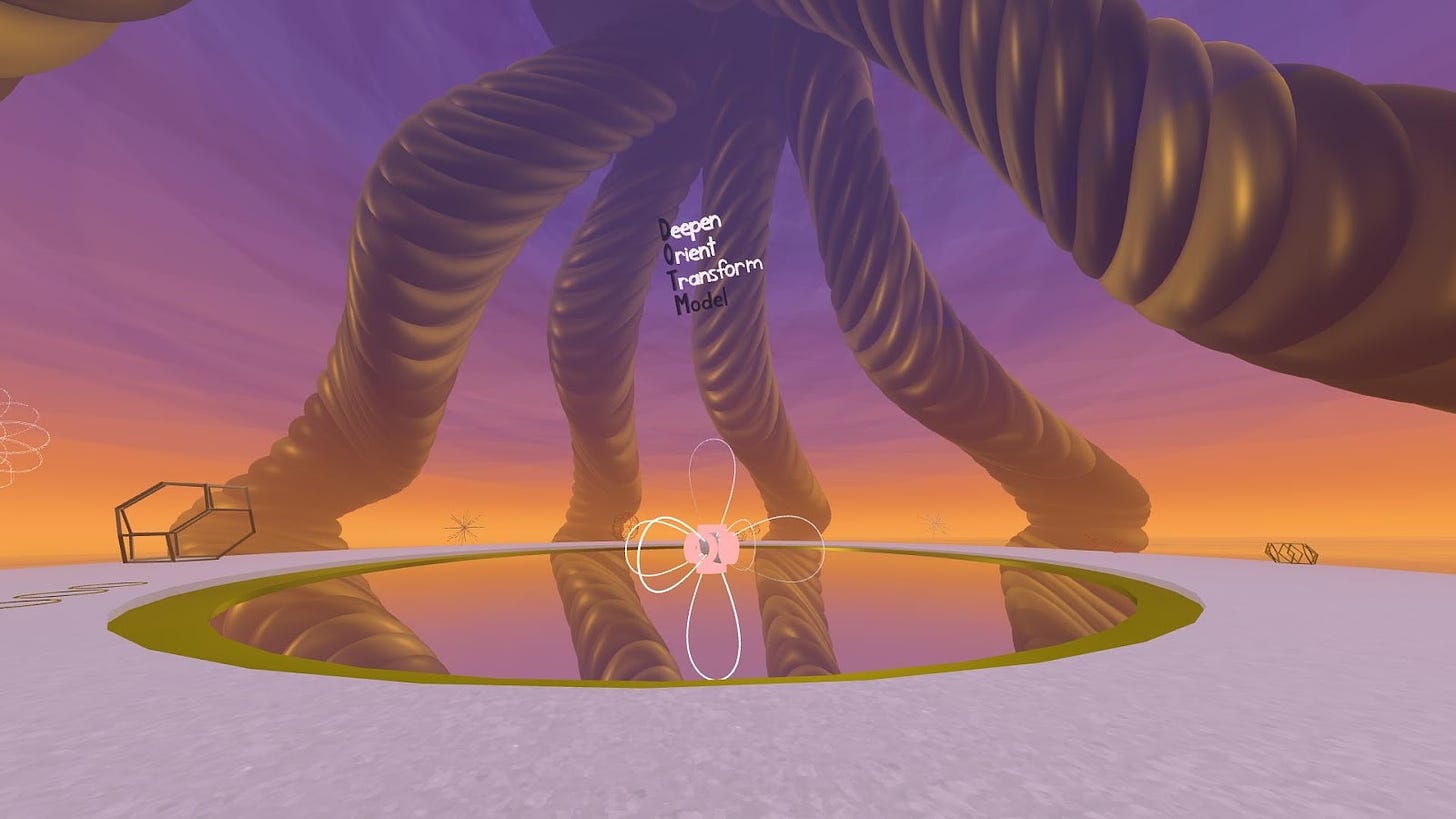

The Deepen Orient Transform (DOT) model was developed by Dr. Diaz. For more information on the DOT model, read here and watch below:

After hearing more about your recent conflict and how you explained it through this terminology, I wanted to ask this question for our audience to learn about it: What is community debt?

Yeah, I'm happy to explain that. I want to acknowledge my own community debt because I'm in a place of grief around it right now. There’s this huge discrepancy between all the healing, helping, and loving I’ve done over the past three years for complete strangers—who never felt like strangers to me—and what I’ve gotten in return. It’s like being a mountain and being upset that someone with a tiny pot of dirt didn’t add some of their dirt to the mountain.

People come into social VR with incredible deficits, very early in their development of sensing who they are, and building a self they can eventually let go of. You can’t let go of yourself until you’ve built it, and you can’t stay conscious of that cycle of letting go until you feel solid. And it’s hard to feel solid in a place like this. I say this with all the forgiveness in the world. The term “community debt” has existed in verbal conversations in the community management field for at least a few years. People are familiar with it, but it was never written down or clearly defined.

One of the results of the implosion of the community I built—which completely collapsed last year—was realizing that this term needed to be actualized and written down. Not having those words to describe the suffering and pain could have created an even bigger misunderstanding in me and others about what had happened. Without the term "community debt," it’s easy to fall back on labels like trolls, influencers, bad actors, villains, or soulless corporations. Those are the terms that exist when community debt isn't understood.

So, what I’ve learned is that community debt arises when there’s a product, like the application we’re in, or an actual thing. Communities grow around the thing offered by a company because they have a need for it. But in order to keep that community, the company must give more than just the product. They try to offer other nutrients or incentives to get the community to actually build something, not just consume.

The first misunderstanding that leads to community debt is when companies believe that consumers are the same as a community. To be a consumer is one-directional—I’m a baby bird, you feed me, and I sing back about how good the food is. But to build community, communication must go both ways. I have to help you rebuild the nest. I need to give you feedback that makes the nest better. To do that, I must trust you and know your humanity, not just see you as a company or organization. I need to know you’re worthwhile and empowering.

Community debt builds when companies see their consumers as a community, but they don’t invest in offering the other nutrients that community needs to grow healthy, resilient relationships. Over time, this creates deficits—like pirates who would die from vitamin deficiencies when they just needed an orange. Community debt builds when these deficits grow, and leaders emerge from the blind spots the company isn’t conscious of. The company thinks, They like our product, therefore they are a community, and they don’t engage in growing rituals, values, or community leaders.

Instead, they focus on influencers, because influencers are controllable—they're attached to the power the company gives them. If the company wants to change their statements, they can move influencers where they want. But community leaders hold loyalty to the community first, which can be a threat to the company. As a result, community leaders get marginalized and ignored, while influencers are amplified.

Community debt grows when influencers gain power while community leaders absorb the shadow of what's happening. Wars break out between influencers and community leaders, and people exit the community because they can feel the tension. The disingenuousness of the influencers, who are being rewarded, and the burnout of the community leaders, who eventually leave, leads to collapse. I believe community debt was the main cause of what happened last year.

Community debt is what happens when companies don’t grow rituals to engage their communities, don’t invest in values, and don’t support community leaders who are building those values. Or keeping everyone re-humanizing themselves and practicing releasing privilege. We all have privilege to release, but how we assess and offer that privilege is a messy, hard-to-predict process, and companies don’t have good OKRs (objectives and key results) or ROIs (return on investment) around it.

I’ve also been working on the concept of emotional debt, which is different but related. We all have emotional debt—a kind of accidental quid pro quo, where we have expectations related to how we serve each other and the emotions we receive in return. I didn’t realize how much emotional debt I had built up until recently. I thought I had been clear about my needs: I needed help building this model to give it to the world. Instead, I’ve been harmed, targeted, torn apart, and had my life destroyed in every way except that I’m still breathing.

At the same time, for the first time in three and a half years, when I pulled the trigger on this group of cubes programmed to activate the DOT model, it started to grow on its own for the first time, instead of me having to hand place the pieces every time. I’m grateful for that. Last Sunday, I ran my first workshop where I was able to just pull the trigger and talk through a PowerPoint. It’s primitive, but it’s better than it’s ever been. And yet, it’s devastating to see how long it took to get to this point, and how little help I received from the people I’ve supported. So I’m letting that go. The model has been an incredible catalyst for emotional centering through unpleasant experiences, and it’s helped me build more conscious relationships. But I did get stuck with some community and emotional debt along the way, and by naming it, I hope to release it and set better boundaries. In the end, I’m not special in that respect. We all have moments where we give everything and get nothing, or even harm, in return. That’s a painful realization, but it’s part of the human story.

You can read Part 2 of our interview with Ruth on Monday, September 23rd!